LONG TERM NATURE OF THE CONTRACT AND HOW TO MANAGE COUNTER PARTY RISK

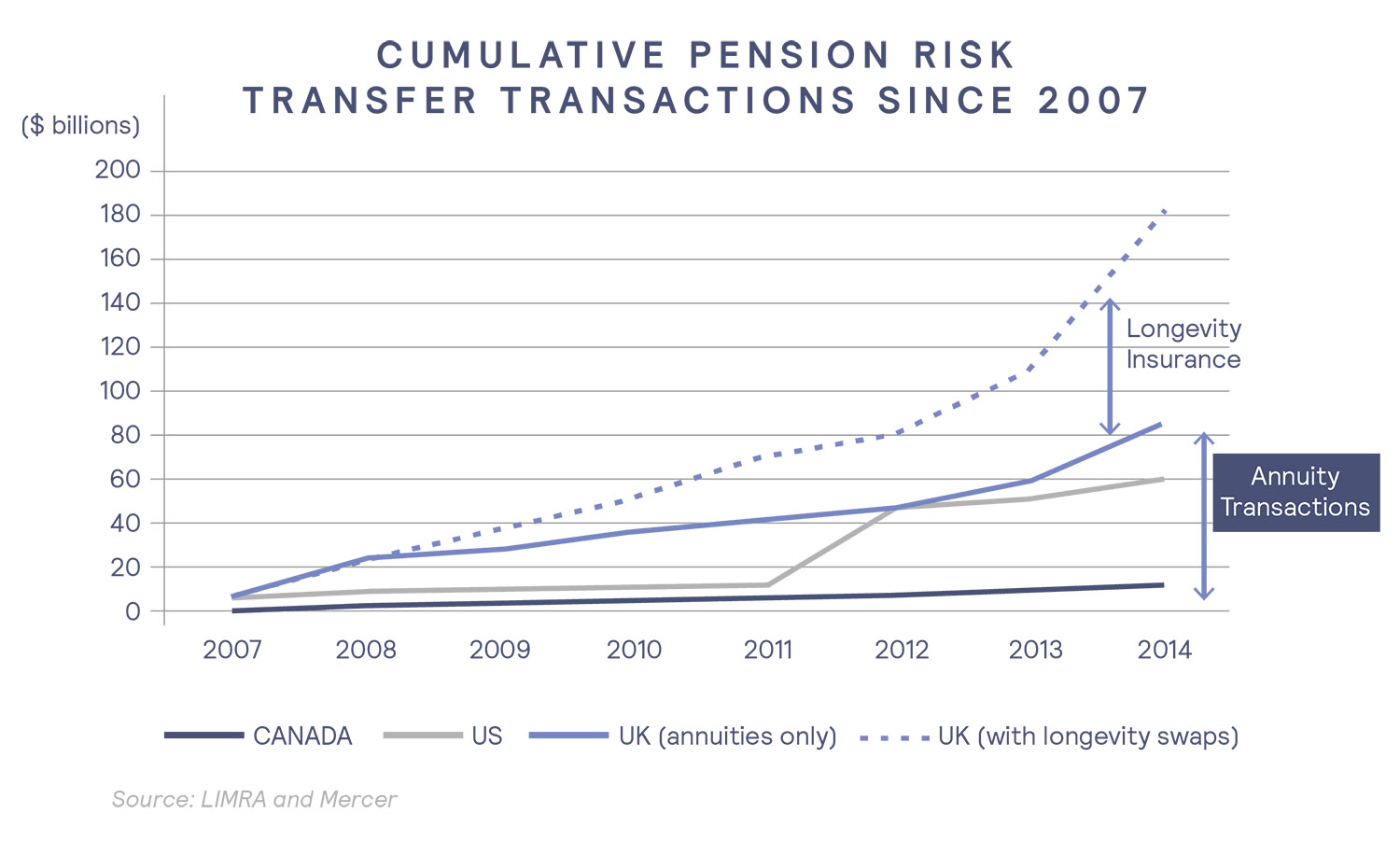

As opposed to an annuity purchase where the premium is paid up-front, in a longevity swap the premium is paid monthly as part of the fixed leg and risk exposure is symmetrical (either party might be obligated to pay depending on the actual longevity of covered pensioners). However, payment of what is owed to the party “in-the-money” will only be paid over time as expectations are, or are not, realized. This deferred nature of the settlement payments introduces counterparty risk to the side that believes that future experience will be in its favour. This issue can be of particular concern in cases where there is a strong indication that the current best-estimate assumption is incorrect but experience has yet to emerge as may be the case, for example, following the spread of a deadly disease or discovery of a cure for cancer.

Consequently, longevity swaps usually contain some form of protection against the other party’s inability or unwillingness to pay. In the United Kingdom, where the longevity swap is more common, traditional practice has been to establish collateral accounts for both the fees payable by the insured to the insurer and the experience amount that is expected to be paid in the future. These accounts tend to be valued daily with every dollar of risk exposure collateralized. However, other credit risk mitigation techniques can also be used.

Alternative strategies have included “resetting” the fixed leg with a cash payment to reflect the revised mortality assumption once experience begins to stray too far from expected or using a collateral account approach but with significantly high thresholds to limit the frequency of having to post collateral.

Ultimately, the structure of the counterparty credit risk mitigation and the extent to which it serves as protection should not be predetermined but rather negotiated among all parties and customized on a deal-by-deal basis.

Although the mechanics of the process remain the same, a longevity swap can be structured as either an insurance product or as a bank derivative. A swap classified as an insurance product will generally fall under insurance legislation and be subject to their capital requirements. This might be particularly onerous when trying to include a foreign reinsurer, as they too will be subject to these regulations. A longevity swap that is designed to be a derivative product will be governed by an ISDA (International Swap and Derivative Association) agreement signed between the two parties.

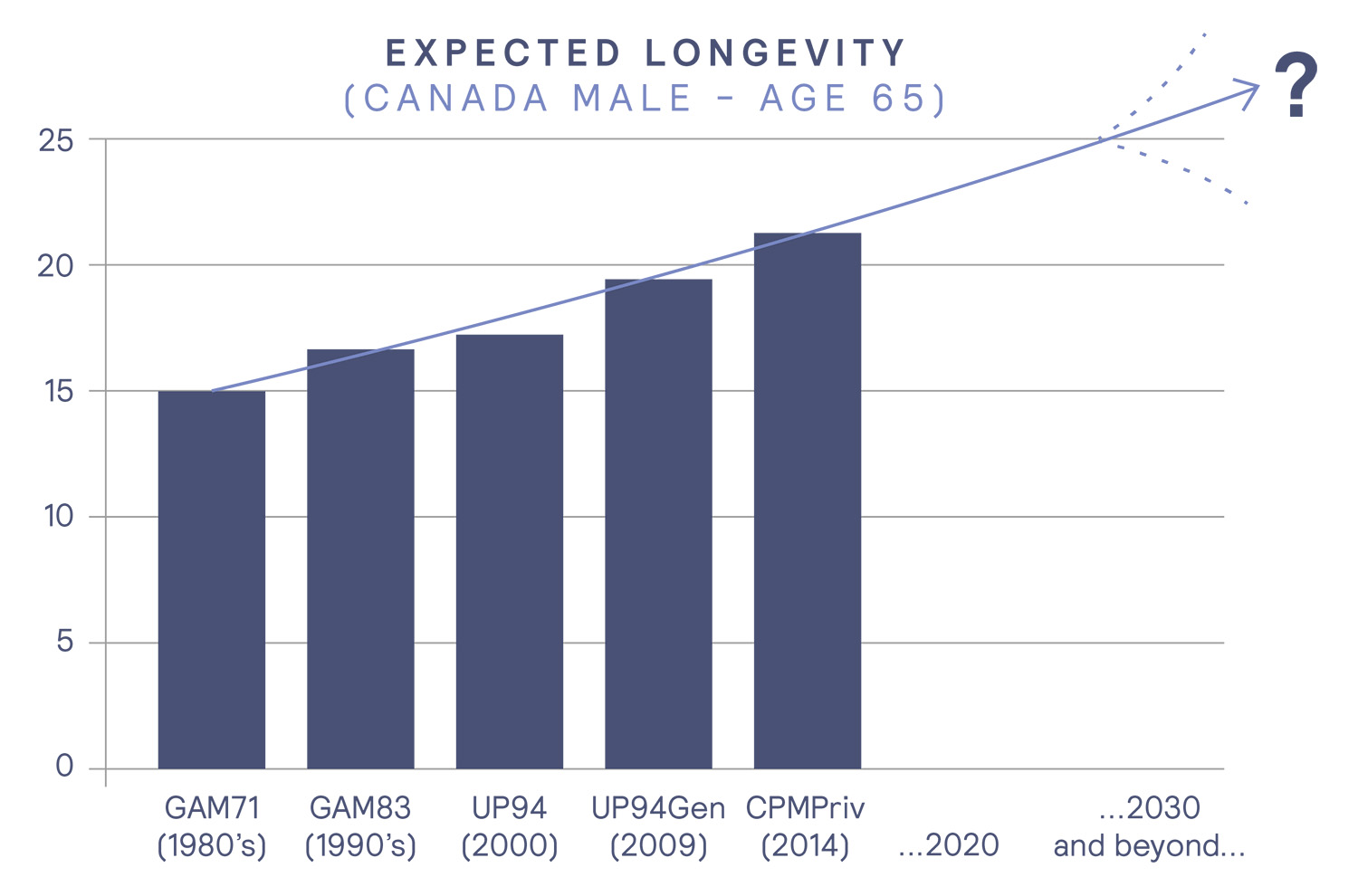

Recently, longevity swaps have started gaining traction in Canada. In March 2015, Bell Canada announced that it had entered into a longevity swap with Sun Life. This was the first transaction of its kind completed outside of the UK. With an underlying face value of $5 billion CAD, it was the largest de-risking transaction ever done in Canada and the 5th largest globally.

Looking at pension plans going forward, care must be taken not to disregard the potential loss due to adverse longevity experience. That’s not to say that every plan must act to hedge this risk – different plans have different risk profiles and different plan sponsors have different risk appetites. However, we must acknowledge that this exposure exists and plan accordingly. We must act like the wise frog from Aesop’s fable and learn from our past mistakes. We must think before we leap.